Home » Posts tagged 'Food'

Tag Archives: Food

Super Size Me – science or balderdash

Many students have seen the 2004 documentary “Super Size Me” in a health class. Is this film a fair illustration of the harmful effects of fast food, or is it junk science, misleading, and possibly deceptive?

Super Size Me is directed by and starring Morgan Spurlock. The movie follows a one month period during which he ate only very large portions of McDonald’s food.

“The film documents this lifestyle’s drastic effect on Spurlock’s physical and psychological well-being and explores the fast food industry’s corporate influence, including how it encourages poor nutrition for its own profit.” (Wikipedia)

The most common criticism is that eating fast food doesn’t cause weight gain; in fact several people had demonstrated sustained weight loss while eating a McDonalds-only diet. The weight gain came from deliberate, daily binging.

A deeper criticism is a rejection of his claim that fast food causes liver damage in just one month. In fact, Morgan Spurlock later admitted that he was a lifelong alcoholic, and it is believed that this behavior which caused the liver issues he spoke about at the end of his film.

Ken Hoffman writes

Now comes comedian-writer Tom Naughton with Fat Head, a new documentary that he’s shopping around to distributors. In Fat Head, Naughton plows head first into fast food and doesn’t come up for air for 30 days. It’s similar in premise to Super Size Me and is just as funny but with a very different ending.

Naughton loses 12 pounds (206 to 194) and his cholesterol goes down (231 to 222, which still isn’t good, but better)…

Naughton lost weight stuffing his face with burgers. Basically, he went on a modified Atkins low-carb diet. He ate the burger but tossed most, if not all, of the bun. Unlike Spurlock, Naughton has a page on his Web site that lists every item (including nutritional information) he ate during his fast-food month.

Ordering up some food for thought, Ken Hoffman, Houston Chronicle, 1/15/2008

Soso Whaley showed that if one made reasonable dietary choices then one could eat every day at McDonalds, lose weight, lower one’s cholesterol level, and stay healthy. She writes:

Even without seeing the film I could tell from the clips and the description by Spurlock that this was nothing more than junk science masquerading as legitimate scientific discovery…. Super Size Me should not be allowed to exist without a proper counterpoint to it’s blatant propagandizing and shoddy scientific methodology. Other than that, I wanted to lose ten pounds.”

“…no, McDonald’s isn’t what is considered to be a “politically correct” source of food in our current cultural climate. However, when I was growing up during the 50s and 60s we didn’t have all the tens of thousands of food choices available today. Back then a hamburger or a chicken sandwich was considered a legitimate way to acquire a serving of high-grade protein and grains, add a tomato and some lettuce, maybe a little onion, pour an 8 oz. glass of milk and you have what would be considered a pretty healthy meal, provided you use proper serving sizes.

So from my point of view McDonald’s serves food that is no better or even different than that which I could acquire at the local store or pretty much any other restaurant”

“To be honest this film is not about bucking up McDonald’s, just a close look at what happens when a person engages in a lifestyle which includes common sense and personal responsibility. I understand that these concepts are very scary to those individuals and corporations who rely on our fear and lack of education to make a buck.

It’s time to take a stand against these food cops and health nannies who won’t be happy until we are eating only food approved by a small group of people who claim to have our best interests at heart but whose real agenda seems to be more about scaring people than in truly educating the public. Spurlock is merely an agent of those who would seek to control our lives and limit our choices “for our own good”.”

“Yes, I lost weight and have managed to maintain that loss. The first time I did the diet in April 2004, I lost 10 pounds (going from 175 to 165) and lowered my cholesterol from 237 to 197, a drop of 40 points. I did the diet again in June 2004 and lost another 8 pounds (going from 165 to 157), there was no change in my cholesterol during that time as it remained at around 197. “

Soso, So Good, National Review Interview, 6/3/2005

==========

Bob Carlton writes

Iowa high school science teacher John Cisna weighed 280 pounds and wore a size 51 pants. Then he started eating at McDonalds. Every meal. Every day. For 180 days. By the end of his experiment, Cisna was down to a relatively svelte 220 and could slip into a size 36.

Cisna left it up to his students to plan his daily menus, with the stipulation that he could not eat more than 2,000 calories a day and had to stay within the FDA’s recommended daily allowances for fat, sugar, protein, carbohydrates and other nutrients. A local McDonald’s franchisee agreed to provide the meals.

“Every time we try to throw the fast-food industry under the bus, it enables fat people like me to say, ‘That’s why I’m fat; McDonald’s makes me fat. Burger King makes me fat,'” Cisna said. “But in all those years that I was fat, I hardly ate fast food. I got that way eating from a grocery store, and from restaurants.

“As a science teacher, I would never show ‘Super Size Me’ because when I watched that, I never saw the educational value in that,” Cisna said. “I mean, a guy eats uncontrollable amounts of food, stops exercising, and the whole world is surprised he puts on weight?’

“What I’m not proud about is probably 70 to 80 percent of my colleagues across the United States still show ‘Super Size Me’ in their health class or their biology class. I don’t get it.”

Meet the science teacher who lost 60 pounds eating nothing but McDonald’s three meals a day, Bob Carlton, 8/11/2015, updated 1/13/2019

==========

In the Wall Street Journal, Phelim McAleer writes that some central points of Super Size Me seem to be bogus:

Before the 30-day experiment, he said, he was in a “good spot” healthwise. By the experiment’s end, he reported experiencing fatigue and shakes (trembling, not Shamrock). Most disturbing, and most widely reported, was that he had suffered liver damage.

The New York Times review was headlined “You Want Liver Failure With That?” The doctor examining him during the experiment said the fast food was “pickling his liver” and that it looked like an “alcoholic’s after a binge.”

Fast-forward to December 2017, when Mr. Spurlock issued a #MeToo mea culpa titled “I Am Part of the Problem,” detailing a lifetime of sexual misdeeds. As a result, YouTube dropped its plans to screen his “Super Size Me” sequel, and other broadcasters cut ties. But overlooked in all this was a stunning admission that calls into question the veracity of the original “Super Size Me.”

After blaming his parents for his bad acts, Mr. Spurlock asked: “Is it because I’ve consistently been drinking since the age of 13? I haven’t been sober for more than a week in 30 years.”

Could this be why his liver looked like that of an alcoholic? Were those shakes symptoms of alcohol withdrawal? Mr. Spurlock’s 2017 confession contradicts what he said in his 2004 documentary.

“Any alcohol use?” the doctor asks at the outset. “Now? None,” he replies. In explaining his experiment, he says: “I can only eat things that are for sale over the counter at McDonald’s—water included.”

A Big Mac Attack, or a False Alarm? Phelim McAleer, 5/23/2018, Wall Street Journal

==========

“All Mr. Spurlock demonstrated is that gluttony does not lead to weight loss. We already knew that.”

– Dr. Ruth Kava, ACSH nutrition director

Health Panel: “Supersize Me” Movie Trivializes Obesity, A Serious Problem, American Council on Science and Health, 5/6/2004

==========

Kate Douglas writes

By the end of Spurlock’s McDonald’s binge, the film-maker was a depressed lardball with sagging libido and soaring cholesterol. He had gained 11.1 kilograms, a 13 per cent increase in his body weight, and was on his way to serious liver damage.

In contrast, Karimi had no medical problems. In fact, his cholesterol was lower after a month on the fast food than it had been before he started, and while he had gained 4.6 kilos, half of that was muscle. …

Supersize me’ revisited – under lab conditions, Kate Douglas, New Scientist, 1/2007

Archived versions of that article may be read here:

https://skylertanner.com/2010/04/30/supersize-me-revisted-under-lab-conditions/

https://forum.bodybuilding.com/showthread.php?t=1316711

Learning Standards

2016 Massachusetts Science and Technology/Engineering Standards

Students will be able to:

* apply scientific reasoning, theory, and/or models to link evidence to the claims and assess the extent to which the reasoning and data support the explanation or conclusion;

* respectfully provide and/or receive critiques on scientific arguments by probing reasoning and evidence and challenging ideas and conclusions, and determining what additional information is required to solve contradictions

* evaluate the validity and reliability of and/or synthesize multiple claims, methods, and/or designs that appear in scientific and technical texts or media, verifying the data when possible.

A Framework for K-12 Science Education: Practices, Crosscutting Concepts, and Core Ideas (2012)

Implementation: Curriculum, Instruction, Teacher Development, and Assessment

“Through discussion and reflection, students can come to realize that scientific inquiry embodies a set of values. These values include respect for the importance of logical thinking, precision, open-mindedness, objectivity, skepticism, and a requirement for transparent research procedures and honest reporting of findings.”

Next Generation Science Standards: Science & Engineering Practices

● Ask questions that arise from careful observation of phenomena, or unexpected results, to clarify and/or seek additional information.

● Ask questions that arise from examining models or a theory, to clarify and/or seek additional information and relationships.

● Ask questions to determine relationships, including quantitative relationships, between independent and dependent variables.

● Ask questions to clarify and refine a model, an explanation, or an engineering problem.

● Evaluate a question to determine if it is testable and relevant.

● Ask questions that can be investigated within the scope of the school laboratory, research facilities, or field (e.g., outdoor environment) with available resources and, when appropriate, frame a hypothesis based on a model or theory.

● Ask and/or evaluate questions that challenge the premise(s) of an argument, the interpretation of a data set, or the suitability of the design.

Thanks for visiting my website. We also have resources here for teachers of Astronomy, Biology, Chemistry, Earth Science, Physics, Diversity and Inclusion in STEM, and connections with reading, books, TV, and film. At this next link you can find all of my products at Teachers Pay Teachers, including free downloads – KaiserScience TpT resources

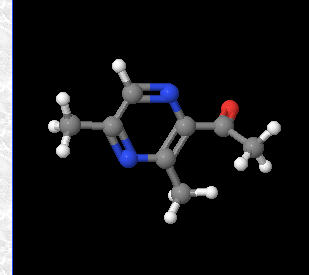

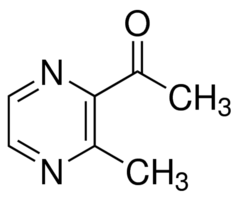

Organic molecules in smoke

Burning wood produces a wide array of organic compounds. Each type of wood makes many unique compounds, and the specific compounds formed depend on the amount of oxygen available. Here are a few of them.

Description: nutty roasted hazelnut

—-

nutty nut flesh roasted hazelnut toasted grain

sigmaaldrich.com

Learning Standards

2016 Massachusetts Science and Technology/Engineering Curriculum Framework

HS-LS1-6. Construct an explanation based on evidence that organic molecules are primarily composed of six elements, where carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen atoms may combine with nitrogen, sulfur, and phosphorus to form monomers that can further combine to form large carbon-based macromolecules.

Meaningless words in food science

4 meaningless words: toxin, natural, organic, and GMO

Archived for my students. From The Logic of Science, 8/16/2016

News articles and blog posts are often full of buzzwords that are heavy on emotional impact but light on substance, and for scientific topics such as nutrition, health, medicine, and agriculture, four of the most common buzzwords are “toxins,” “natural,” “organic,” and “GMO.”

These words are used prolifically and are typically stated with clear implications (“toxin” and “GMO” = bad; “natural” and “organic” = good).

The problem is that these words are poorly defined and constantly misused.

They are often used in a way that shifts them into the category of what are referred to as “weasel words,” meaning that their use gives the impression that the author said something concrete and meaningful, when in fact the statement was a null sentence that lacked any real substance.

“Toxins”

Our society seems to be obsessed with “toxins.” The internet is full of purveyors of woo selling everything from expensive fruit cleanses to “earthing” mats, all with the intended purpose of ridding your body of vaguely defined “toxins.”

The problem is simply that there is no such thing as a “toxin.” All matter is made of chemicals (excluding subatomic particles for a minute), and essentially all chemicals are safe at a low enough dose and toxic at a high enough dose (i.e., the dose makes the poison).

So there are toxic doses not toxic chemicals. Even water becomes lethally toxic at a high enough dose (Garigan and Ristedt 1999). So this idea that something is going to rid your body of “toxins” doesn’t make any sense, because the chemicals themselves are not “toxins,” and they only become toxic at a high enough dose.

Take formaldehyde, for example. I often hear people talk about it as a “toxin,” but the reality is that it is an inevitable bi-product of normal biological processes. So not only is it in many fruits and vegetables, but it is actually produced by your body! The chemical itself is not dangerous, but it can become dangerous at a high enough dose.

To be clear, I’m not saying that we shouldn’t pay attention to what we put into our bodies. Of course we should, but we need to evaluate chemicals based on the dose at which they become toxic, not simply based on whether or not they are present.

Addendum (16-Aug-16): “Toxin” does have an actual biological meaning in the context of chemicals that are released by microscopic organisms. These are often toxic to individual cells at incredibly low doses because a cell itself is so small. So when I talked about “toxins” in the post, I was referring to the notion that certain chemicals are automatically dangerous for you as an organism, rather than on a cell by cell basis.

“Natural”

The definition of “natural” seems obviously to be, “found in nature,” but that’s actually a lot more ambiguous and arbitrary than it sounds. First, let’s deal with why this definition is arbitrary, and the best way to explain that is by talking about chemical compounds.

Everything around you is made of chemicals (including you)

In chemistry, a compound is simply the combination of two or more different elements. So most of the things that are around you are in fact chemical compounds (there are several thousand compounds that make your body, for example).

Now, many people like to distinguish between “natural” and “synthetic” chemicals, where “natural” chemicals can be found in nature, while “synthetic” ones were produced in a lab, but that distinction is arbitrary. A chemical is a chemical, and on a molecular level, there is nothing that separates natural and synthetic chemicals.

All chemical compounds are made by stringing different elements together, and there is no inherent difference between nature stinging elements together and scientists stringing elements together. We can make acids in the lab and you can find acids in nature, we can make chemicals that are poisonous at anything but a low dose in the lab, and you can find chemicals that are poisonous at anything but a low dose in nature, etc.

The fact that something was synthesized in a lab doesn’t make it any more dangerous or any safer than a chemical that was found in nature.

Consider, for example, acetylsalicylic acid and salicylic acid. One of those is natural and the other is synthetic.

Can you tell which? No, and neither could a chemist. If you showed those two molecules to a chemist who had no prior information about those chemicals, there is no way they she could tell you which was natural and which was synthetic, because that distinction is arbitrary.

In all likelihood though, she would know which is which because these are two very well-known compounds. Salicylic acid is the compound in willow bark that gives it medicinal value, and acetylsalicylic acid is the synthetic version of it that we all know as aspirin.

Further, we switched to the synthetic version largely because straight salicylic acid has a lot of unpleasant side effects like gastrointestinal problems (Hedner and Everts 1997).

To be clear, aspirin has side effects as well (as do all chemicals), but they tend to be less severe, and the point is, once again, that simply being natural doesn’t automatically make something better. Indeed, asserting that something is better because it is natural is a logical fallacy known as an appeal to nature.

Moving beyond the arbitrariness of what is natural, the typical definition of “found in nature” doesn’t apply to some things that most people would intuitively think of as natural.

Take apples, for example. They’re natural, right? Not so much. The fruit that we know as an apple does not grow in nature. As I will talk about more later, essentially all of our crops have been modified by thousands of years of careful breeding, so, technically speaking, they aren’t natural.

The situation is even more problematic when we talk about actions rather than objects. People often say things like, “we should do X, because X is natural,” but what on earth does that mean?

Generally, I hear people say that it means what our ancestors did, but that raises the obvious question of how far back do we have to go for something to be natural? Are we talking about 200 years ago? 1,000 years ago? 10,000 years ago? etc. This definition is horribly ambiguous.

To get around this problem, some people say that natural actions are those that are found in the animal kingdom, but that is also an extremely problematic definition for a number of reasons.

First, how widespread does it need to be in the animal kingdom? Is it simply required to find one animal that does it? Further, there are lots of human actions that most people think of as natural, even though other animals don’t do them. For example, we cook our food. Does that making cooking unnatural?

Finally, this definition is fundamentally flawed because we are just highly evolved animals, so doesn’t that make everything that we do natural? Actually think about this for a second. I think that we can all agree that structures like bird nests and beaver dams are natural, but those are not structures that just form spontaneously in nature. Rather, they are carefully and deliberately constructed by an animal who uses materials to make them.

Nevertheless, if I make a wooden table, most people would agree that the table is unnatural, but how on earth is that any different from a beaver dam? The beaver is an animal that took materials found in nature and combined them to make a new structure, and I am an animal that took materials found in nature and combined them to make a new structure. What’s the difference?

Further, we can logically extend this to all human structures. When you get right down to it, all of the parts of a skyscraper came from nature, and there is no logical reason to say that a beaver combining sticks and mud to make a dam is natural but me combing two metals to make steel is unnatural. Again, the definition of natural is completely arbitrary and functionally meaningless.

“GMO”

GMO stands for “Genetically Modified Organism,” and you may think that this has a very clear and precise definition…but it really doesn’t. Before reading the rest of this, try to come up with a definition of it yourself, then see how that definition holds up.

The most general line of thought would be that a GMO is exactly what is says: “an organism whose genes have been altered,” but that definition is much too broad.

Every living organism has a genetic code that has been altered from its ancestral state by millions of years of evolution. If you really think about it, we are all just heavily modified cyanobacteria (cyanobacteria [or some similar organisms] where most likely the first living cells).

Now you may think that I am stretching things a bit here, and perhaps I am, but “nature” does all sorts of crazy things like hybridizing species (as plants do frequently) and even stealing the DNA from one organism and inserting it into the genetic code of another.

For example, at some point in the evolution of the sweet potato, it managed to modify its genetic code by inserting bacterial genes into its DNA. In other words, it is a transgenic species whose genetic code is a combination of the genes of several species. Shouldn’t that make it a GMO?

Further, this is not limited to sweet potatoes, because bacteria themselves are well known for their ability to incorporate the DNA of other species into their own genomes. So nature is constantly doing the types of things that most people would associate with GMOs, and foods like sweet potatoes really are transgenic species.

Nevertheless, you can try to qualify the term GMO by saying that GMOs are, “organisms that have been genetically modified by humans,” but that definition is also fraught with problems. Beyond the fact that it is totally arbitrary (see the “natural” section), it also would encompass all modern agriculture.

Those delicious fruits that you know as watermelons don’t exist in nature (at least not in their current form). Similarly, natural bananas are small and full of giant seeds, and wild corn does not produce those nice juicy husks that you slather in butter and salt. Both our livestock and crops have been genetically modified through years selective breeding, and they contain genetic codes that aren’t found in nature.

[All the “natural” corn we eat has been extensively genetically modified by thousands of years of artificial selection.]

At this point, people often try to add something about moving genes between species, but that just creates more problems. First, nature does that as well…

Second, that would also include lots of “non-GMO” crops such as pluots, plumcots, tangelos, etc. all of which are hybrids that used selective breeding to combine the DNA of two different species.

Given the problems with that definition, you might try defining a GMO as an organism that is “modified by humans via a method other than selective breeding,” but that definition includes mutation breeding, which is typically not considered to be a GMO.

This method uses chemicals or UV radiation to randomly mutate organisms’ DNA in order to produce new and useful traits (i.e., it makes genetic modifications via inducing mutations). However, this method typically does not receive the label “GMO,” and in some cases, even farms that label themselves as “organic” can us crops that were produced by this method.

This leaves us with the outrageous definition that a GMO is, “an organism whose DNA was modified by humans via a method other than selective breeding or mutation breeding,” but at that point we have tacked so many arbitrary qualifiers onto the term, that the term itself is essentially meaningless.

“Organic”

Finally, let’s talk about the term “organic.” This is perhaps the greatest marketing term ever coined, and the problem with it is not that a definition doesn’t exist, but rather that the definition is arbitrary and most people don’t use it correctly (to be clear, I am talking specifically about organic farming practices, not organic chemistry.)

Here is a question for you, true or false, organic farming doesn’t use pesticides?

Organic farmers absolutely use pesticides, and many of those pesticides are toxic at comparable doses to the pesticides used in traditional farming.

Indeed, organic pesticides have can harm wild species, pollute waterways, and do all of the other harmful things that traditional pesticides can do (Bahlai et al. 2010). In fact, one of the most common organic pesticides is “Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) toxin,” which is the exact same chemical that GMO corn produces (i.e., Bt maize).

So one the one hand, organic farmers use Bt liberally, and on the other hand, they demonize corn that produces Bt. Are you starting to see why this is arbitrary ?

So if organic crops use potentially dangerous pesticides just as much as traditional crops, then what exactly does it take for a crop to be considered organic? Generally speaking, they have to be grown without synthetic pesticides (“natural” are fine) and without the use of GMOs (some countries place additional requirements like no petroleum-based fertilizers). …

Yet distinction between “natural” and “synthetic” chemicals is arbitrary and all chemicals are safe at a low dose and toxic at a high enough dose… and the term GMO is really arbitrary. So, since the definition of organic relies on those other terms, the “organic” label is itself arbitrary.

To put this another way, organic crops are not automatically healthier or more nutritious than traditional crops. Indeed, reviews of the literature have been unable to find consistent and compelling evidence that organic food is healthier (Smith-Spangler et al. 2012; Galgano et al. 2015).

Now, at this point, you may be thinking that organic crops aren’t healthier, but surely they are better for the environment. However, that is also a misnomer. Some practices that are typically associated with organic farming are better for the environment, but those practices are sometimes included in non-organic farming as well, and organic farming has serious drawbacks, such as the fact that it often uses far more land and resources than traditional farming (Tuomisto et al. 2012).

As a result, you can’t make a blanket statement like, “organic farming is better for the environment” because in many cases it isn’t.

The point is that simply saying that something is “organic” doesn’t actually tell you anything useful about how healthy it is or whether or not it was grown in a sustainable way.

Also see https://thelogicofscience.com/2015/11/16/the-real-frankenfoods/

Citations

Bahlai et al. 2010. Choosing organic pesticides over synthetic pesticides may not effectively mitigate environmental risk in soybeans. PLoS ONE 5:e11250.

Doucleff. 2015. Natural GMO? Sweet potato genetically modified 8,000 years ago. NPR: Food and Culture

Garigan and Ristedt 1999. Death from hyponatremia as a result of acute water intoxication in an Army basic trainee. Military Medicine 164:234–238.

Galgano et al. 2015. Conventional and organic foods: A comparison focused on animal products. Cogent Food and Agriculture 2: 1142818.

Hedner and Everts 1997. The early clinical history of salicylates in rheumatology and pain. Clinical Rheumatology 17:17–25.

Ruishalme. 2015. Natural assumptions. Thoughtscapism.com. Accessed 15-Aug-16

Smith-Spangler et al. 2012. Are organic foods safer or healthier than conventional alternatives? A systematic review. Annals of Internal Medicine 157:348–366.

Tuomisto et al. 2012. Does organic farming reduce environmental impacts? A meta-analysis. Journal of Environmental Management, 112:309–320.

Wilcox. 2011. Mythbusting 101: Organic farming > conventional agriculture. Scientific American.

Related articles

Meaningless words in food science

Nutrients

Organic food and farming

Meaningless words in food science

What we need to know about healthy diets

Healthy meal generator

This website is educational. Materials within it are being used in accord with the Fair Use doctrine, as defined by United States law.

§107. Limitations on Exclusive Rights: Fair Use. Notwithstanding the provisions of section 106, the fair use of a copyrighted work, including such use by reproduction in copies or phone records or by any other means specified by that section, for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship, or research, is not an infringement of copyright. In determining whether the use made of a work in any particular case is a fair use, the factors to be considered shall include: the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes; the nature of the copyrighted work; the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

(added pub. l 94-553, Title I, 101, Oct 19, 1976, 90 Stat 2546)

Evolution of cereals and grasses

What are cereals and grains, and where do they come from?

A cereal is any grass – yes you read that correctly, grass – cultivated for the edible components of its grain.

Common grasses that produce these wonderful grains are wheat, rye, millet, oat, barley, rice, and corn.

Wheat is the most common grain producing grass.

(botanically, a type of fruit called a caryopsis), composed of the endosperm, germ, and bran.

The term may also refer to the resulting grain itself (specifically “cereal grain”).

Cereal grain crops are grown in greater quantities and provide more food energy worldwide than any other type of crop[1] and are therefore staple crops. Edible grains from other plant families, such as buckwheat, quinoa and chia, are referred to as pseudocereals.

All of the grains that we eat have been genetically modified by thousands of years of artificial selection. This includes all wheat, barley, rye, spelt and oats.

Paper 1: “Wheat: The Big Picture”, The Bristol Wheat Genomics site, School of Biological Sciences, University of Bristol

Wheat: The Big Picture – the evolution of wheat

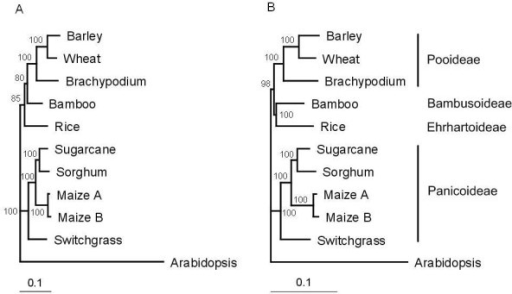

Figure 2. Phylogenetic tree showing the evolutionary relationship between some of the major cereal grasses. Brachypodium is a small grass species that is often used in genetic studies because of its small and relatively simple genome.

Paper 2: Increased understanding of the cereal phytase complement for better mineral bio-availability and resource management

Article (PDF Available) in Journal of Cereal Science 59(3) · January 2013 with 244 Reads

DOI: 10.1016/j.jcs.2013.10.003

Fig. 1. Phylogenetic tree of cereals and selected grasses. PAPhy gene copy numbers are given for each species and key evolutionary events are indicated.

Paper 2

Genome-wide characterization of the biggest grass, bamboo, based on 10,608 putative full-length cDNA sequences.

Peng Z, Lu T, Li L, Liu X, Gao Z, Hu T, Yang X, Feng Q, Guan J, Weng Q, Fan D, Zhu C, Lu Y, Han B, Jiang Z – BMC Plant Biol. (2010)

Figure 2: Phylogeny of grasses inferred from concatenated alignment of 43 putative orthologous cDNA sequences. (A) Tree inferred from maximal likelihood method. Bayes inference yielded the same topology. (B) Tree inferred from neighbor joining method. Branch length is proportional to estimated sequence divergence measured by scale bars. Numbers associated with branches are bootstrap percentages. Arabidopsis was used as outgroup. Subfamily affiliation of the grasses is indicated at right.

Paper 3 Evolution of corn

Figure 1: The evolutionary stages of domestication and diversification.

From Evolution of crop species: genetics of domestication and diversification, Rachel S. Meyer & Michael D. Purugganan, Nature Reviews Genetics 14, 840–852 (2013) doi:10.1038/nrg3605

http://www.nature.com/nrg/journal/v14/n12/fig_tab/nrg3605_F1.html

Paper 4 text

Brachypodium distachyon: making hay with a wild grass, Magdalena Opanowicz, Philippe Vain, John Draper, David Parker, John H. Doonan

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.2008.01.007

This next image is from Setaria viridis as a Model System to Advance Millet Genetics and Genomics.

By Huang, Pu & Shyu, Christine & Coelho, Carla & Cao, Yingying & Brutnell, Thomas. (2016) Frontiers in Plant Science. 7. 10.3389/fpls.2016.01781.

.